With all the talk of nine-figure LIV contracts and $20 million PGA Tour purses and PIF this and PIP that, it’s easy to forget that ultra-competitive golf wasn’t always such a lucrative profession, even for players near the top of the food chain.

Consider the first Players Championship, which was conducted at Atlanta Country Club, in 1974. When Jack Nicklaus triumphed, he pocketed $50,000 from the $250,000 purse. That’s nothing to sniff at — Nicklaus’ haul is the equivalent of about $320,000 in 2023 dollars — but those figures are still a mere sliver of the fortune the best players stand to make on Tour today.

Jerry Pate wasn’t making any money playing golf in the mid-1970s. That’s because he was still an amateur, and an exceptional one at that. In 1974, then an undergrad at the University of Alabama, Pate won the U.S. Amateur. The next year, he played on the winning U.S. Walker Cup team at St. Andrews with Curtis Strange and Craig Stadler, and finished as low amateur with Jay Haas at the U.S. Open at Medinah. Pate was invited to play in a half-dozen Tour events and almost won two of them.

In 1975, Pate entered the PGA Tour’s Q School and finished as medalist. He had officially arrived. Wilson Sporting Goods took note, signing Pate to a cool $10,000 endorsement deal. The only Wilson staffer with a richer agreement at the time was Sam Snead. For Wilson, Pate proved to be a wise investment. It took him all of about six months as a pro to win the U.S. Open — in 1976 — and before the end of the 1977 season he already had won four Tour titles.

Then, sometime in 1980, as Pate recalls it, his phone rang.

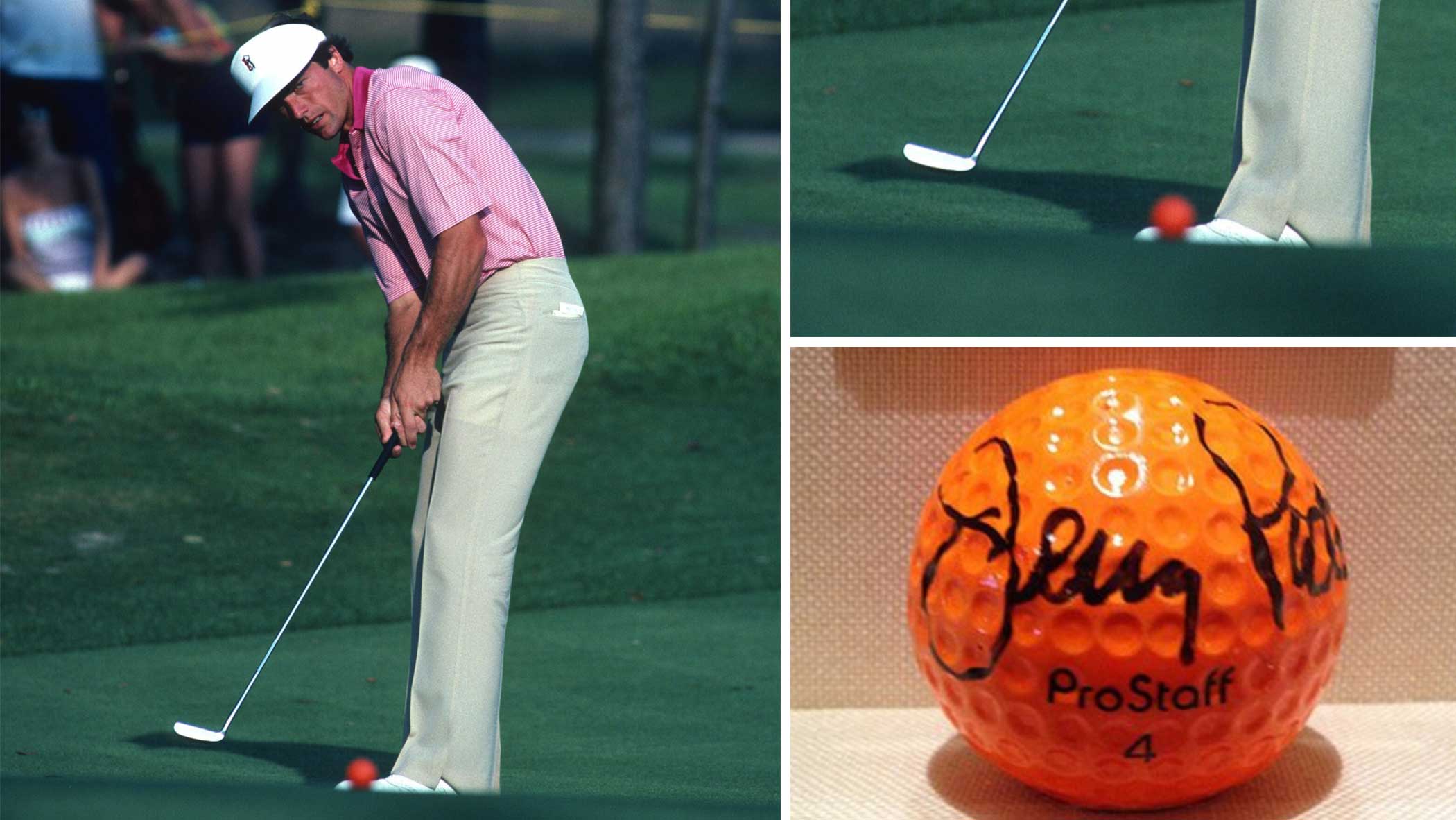

It was Wilson executive Joe Phillips, inquiring whether Pate might be game to demo its new line of orange balls. Pate said he would, and soon after he received a six-figure offer to officially make the balls part of his arsenal.

“I don’t even know why the hell I did it,” Pate, who is 69, said with a chuckle in a phone interview Friday. “They paid me a lot of money and I said, ‘Hey, I’m doing this for a living. I’ll take the money.’”

Pate wasn’t the only Tour player sporting a colored ball — his fellow Wilson staffer Wayne Levi played a yellow ball, with which he won the Hawaiian Open in 1982 — but Pate was easily the most high profile pro to break from the entrenched white-ball tradition.

He said he needed little time to adjust to the color and that the ball’s truncated cone dimples helped with accuracy. Pate added with a laugh, “The biggest advantage was you never hit the wrong ball.”

“People would say to me, ‘How can you putt with that?’” he said. “I realized I don’t even look at the ball when I hit it. It was just kind of down there. You’re thinking more about swing mechanics or the result of the shot more so than the object you’re hitting.”

After Pate won twice in 1981 with the orange balls, PepsiCo, which at the time owned Wilson, featured Pate in a splashy two-page promo in its annual report. “I was hitting a shot out of the bunker with white sand in the background, so the orange ball really stood out,” Pate said. “The headline was something like, Wilson Sporting Goods enjoyed its most profitable year thanks to its sale of orange balls used by Jerry Pate.”

And then came 1982.

The Players Championship was in its ninth year but for the first time it would be contested at the PGA Tour’s new home course, a Pete Dye design at TPC Sawgrass that was collectively owned by the Tour membership. Under the careful watch of PGA Tour commissioner Deane Beman, Dye had built an exacting tournament course unlike any other. It was target golf on acid, and at first most of the players abhorred it.

“All of the players wanted to fire Deane Beman, they wanted to kill Pete Dye, they wanted to immediately sell the golf course,” Pate said. “Nobody liked it. It was too hard, it was too diabolical. But I kind of embraced it. I knew we were on to something with stadium golf. I thought, What the hell, if everyone’s going to bitch and be negative, I’m going to take the Jack Nicklaus route and take the high ground and be positive.”

One positive sign came during the Wednesday pro-am when Pate made a birdie 2 on the island-green 17th. In the first round, he did it again. And again in the second round. He cooled off with a par on Saturday but then made another deuce on Sunday. Four 2s in five tries? It had to be Pate’s week, and it was. He was three back after three rounds but came alive on Sunday, posting a five-under 67 to finish at eight under for the week and beat Scott Simpson and Brad Bryant by two.

How fitting that on a course some of Pate’s peers likened to crazy golf, he prevailed with a ball color more commonly associated with the same pastime.

If Pate was fully sold on his glowing balls, at least one golf power broker was not: legendary CBS Golf producer Frank Chirkinian. Although Pate’s balls were easy to track with the human eye, the same was not true of TV cameras of that era.

“I was on TV a lot,” Pate said. “Played seven years, 77 top 10s. I was on TV near every damn week, and Chirkinian would tell me, ‘Let me tell you something, I can’t see that damn ball.’ He would raise hell, and tell me I need to change balls.”

Pate had no intention of doing so, but the point became moot when soon after his Players win, Pate tore cartilage in his left shoulder, throwing his game into disarray. A year later, he had dropped out of the top 100 players in the world, and by 1987 he was outside the top 200. He had six shoulder surgeries over two decades, none of which allowed him to morph back into the player he had been.

Over time, Pate, who lives with his wife, Soozi, in Pensacola, Fla., began chasing other pursuits, including broadcasting and golf-course design. He also started a business that provides outdoor beautification products to golf courses, municipalities and other businesses, and which now has more than 250 employees. He didn’t fully walk away from competitive golf — he won twice on the PGA Tour Champions, in 2006 and ’08 — but his orange-ball days are over.

And had injuries not derailed Pate’s playing career?

“I would have probably played that ball forever,” he said.